It’s easy to get bored with a programme in which you get stronger with each and every workout. But it’s understandable as they are very repetitive.

The fact you do get sick of these workouts is a pretty good sign that you need to use high-intensity splits in short, strategic increments. As a little goes a long way. Your body makes progress, but your brain knows when you’ve had enough.

So many different types of training, so understandably difficult to know which to choose!

- High volume body-part splits.

- High intensity.

- Low volume splits.

- High frequency training.

- Low frequency training.

- Total body training.

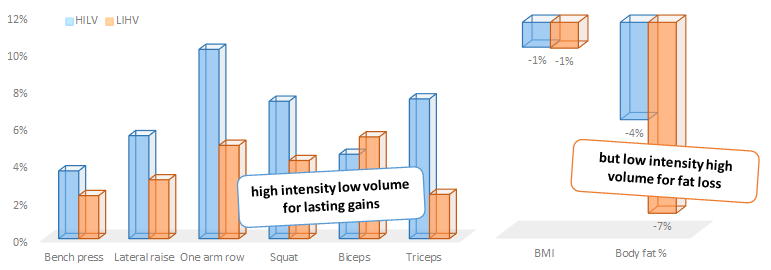

Let me show you how you can take advantage of high-intensity workouts to make huge gains in size and strength. Out of all of them, high-intensity, low-volume training with a body-part split produces dense, granite-like muscle tissue.

Expectations

As with anything else in life that offers big rewards, high-intensity splits have plenty of risks and potential drawbacks. First, as noted, is the boredom, or mental fatigue. Most of us are used to leaving the gym feeling exhausted. With high-intensity splits, you always leave the gym feeling like you could have done more.

More is not better, it’s worse. You’ll get the best results when you resist the urge to do another exercise or do one more set. But there’s an easy way to get around this: When the urge to try something new becomes overwhelming, despite the success of the low-volume program, move on to something different.

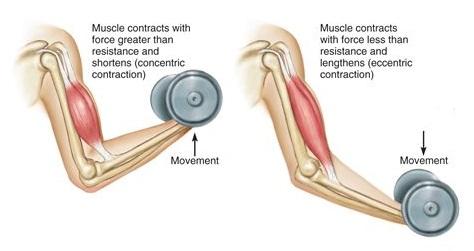

High-intensity training can be tough on your joints. But it doesn’t have to be. You want to lower the weights in a slow and controlled manner on every rep. Make a slow and smooth transition to the concentric part of the lift and accelerate as quickly as possible to activate the maximum number of motor units.

By controlling the negative and changing directions slowly, you’ll limit the stress on your connective tissues. When you follow with a fast and powerful lift, you’ll get maximum stimulation of the muscles you’re targeting.

Finally, stop keeping a training log and recording every rep of every set. If the goal is to top your previous performance, you have to know what that involves. But you’ve trained for years without ever writing anything down. That’s okay for some types of programmes, where the goal is a subjective feeling of muscle exhaustion. It’s not okay for high-intensity split routines.

Every time you walk into the gym, you’re there to beat your performance in your last workout. You have to improve, even if it’s just going up a weight or adding one rep. For that you need to write it down!

Intensity-Boosting Techniques

Straight sets to failure: The most basic way to boost intensity is to train to concentric failure. Continue each set until you can no longer apply enough force to move the weight. You can do two sets of an exercise and occasionally even three sets.

Rest pause: The basic idea is that you extend a set by pausing between reps to allow your muscles to recover. You take a set to concentric failure, re-rack the weight, rest 20 to 30 seconds and do another set to failure. Then you re-rack the weight again, rest and do a final set to failure.

You can use the triple rest-pause (above) set with almost any exercise. The only exceptions are compound, low-back-intensive lifts like squats and deadlifts. One triple rest-pause set per exercise is plenty.

Isometric holds: Completion of your last rep in a set, hold the weight in the contracted position for a long as possible. It’s safe, effective and gives you energy. Iso-holds work best on exercises where there’s tension in the contracted position. It’s really hard to keep yourself at the top of a pull-up, which is why it’s a great exercise for iso-holds. Other exercises, like presses and curls, you can hold the weight for a long time in the top position. So if you were to try iso-holds with these, you need to lower the weight to increase the tension.

If you’re doing multiple sets of an exercise, use an iso-hold for the final rep of the final set.

Partials: These are similar in nature to isometric holds. When you get to the end of a set and can’t complete another full rep, you do a few partial reps to take your muscles to complete exhaustion.

Some of the best exercises for partial reps are calf raises and machine pullovers. So on a bench press, for example, you would use a spotter to help you get the load off your chest after you’ve hit concentric failure. Then you’d do partials in those last few inches before lockout.

As with isometric holds, don’t do more than one set of partials on any given exercise.

Negative reps: When you slowly lower a weight that’s heavier than anything you could move concentrically, you’ll induce more micro-trauma within your muscles than you can with any other training technique. Instead of starting with a weight you can’t lift concentrically, use a weight you can lift multiple times and only use a slow negative after you’ve hit concentric failure.

There is a safe way to make that single negative rep even tougher: Do an iso-hold after your final full-range-of-motion rep and then do the negative. Don’t do this on an exercise in which your knees, shoulders, or lower back would be traumatised. But on lat pull downs or chest-supported rows.

Frequency

Frequency

Volume and intensity have to be inversely proportional. But what about frequency? With lower volume, you should be able to train each muscle group more often. As a general rule, I suggest training each body part once every four to seven days. When you use the intensity-boosting techniques described and which are included in the programme below, once every five to seven days is plenty.

Finish a workout with one set of 15 to 20 reps. Then, as hyperanemic supercompensation (aka the pump) occurs, stretch the muscle for as long as you can stand it. This pump/stretch technique helps expand the fascia around the muscle, giving you a larger muscle belly over time. It also reduces hypertonic adhesions (aka muscle fibres getting stuck to each other), which decrease performance.

Here are workouts for an example of how you can use a variety of high-intensity techniques to train your back.

Back Workout 1

| Exercise | Sets | Reps | Intensity-boosting technique(s) | |

| 1 | Rack deadlift | 2 | 4-6 | Straight sets to concentric failure |

| 2 | Chest-supported row (overhand grip) | 2 | 4-6 | After concentric failure on second set, do an isometric hold and a negative rep |

| 3 | Low-cable row (neutral grip) | 1 | 6-8 | Triple rest-pause set * |

| 4 | Machine pullover | 1 | 15-20 | After concentric failure, do as many partial reps as you can |

Back Workout 2

| Exercise | Sets | Reps | Intensity-boosting technique(s) | |

| 1 | Pull-up | 1 | 6-8 | Triple rest-pause set, finishing with an isometric hold and negative rep * |

| 2 | Barbell bent-over row (underhand grip) | 2 | 4-6 | Straight sets to concentric failure |

| 3 | Lat pulldown (underhand grip) | 1 | 6-8 | Triple rest-pause set, finishing with an isometric hold and negative rep * |

| 4 | Chest-supported reverse flye (lie face-down on an incline bench set to a 30-degree angle) | 1 | 15-20 | After concentric failure, do as many partial reps as you can |

* Choose a weight that you think you can lift 6 to 8 times before you hit concentric failure. Set it down, rest 20 to 30 seconds, then lift again to concentric failure. Set it down again, rest 20 to 30 seconds, lift one more time to concentric failure. In Workout 2, you’ll add an iso-hold to the final rep of the final set, followed by a negative, lowering your body or the weight as slowly as possible.

Do one or two warm-up sets for several of the exercises, especially the first exercise of each workout and any exercise in which you’re doing straight sets to failure.

Train your back once every five to seven days. Do Workout 1 the first time, then Workout 2 the next week and rotate until you decide to change workouts.

Control the weight on each and every rep.

Although the sample workouts are for your back, you can use this template to train any body part.

The shorter the workout, the more focus you need.

Frequency

Frequency